This article first appeared in The Checkup, MIT Technology Review’s weekly biotech newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Thursday, and read articles like this first, sign up here.

Justin Graves was managing a scuba dive shop in Louisville, Kentucky, when he first had a seizure. He was talking to someone and suddenly the words coming out of his mouth weren’t his. Then he passed out. Half a year later he was diagnosed with temporal-lobe epilepsy.

Graves’s passion was swimming. He’d been on the high school team and had just gotten certified in open-water diving. But he lost all that after his epilepsy diagnosis 17 years ago. “If you have ever had seizures, you are not even supposed to scuba-dive,” Graves says. “It definitely took away the dream job I had.”

You can’t drive a car, either. Graves moved to California and took odd jobs, at hotels and dog kennels. Anywhere on a bus line. For a while, he drank heavily. That made the seizures worse.

Epilepsy, it’s often said, is a disease that takes people hostage.

So Graves, who is now 39 and two and half years sober, was ready when his doctors suggested he volunteer for an experimental treatment in which he got thousands of lab-made neurons injected into his brain.

“I said yes, but I don’t think I understood the magnitude of it,” he says.

The treatment, developed by Neurona Therapeutics, is shaping up as a breakthrough for stem-cell technology. That’s the idea of using embryonic human cells, or cells converted to an embryonic-like state, to manufacture young, healthy tissue.

And stem cells could badly use a win. There are plenty of shady health clinics that say stem cells will cure anything, and many people who believe it. In reality, though, turning these cells into cures has been a slow-moving research project that, so far, hasn’t resulted in any approved medicines.

But that could change, given the remarkable early results of Neurona’s tests on the first five volunteers. Of those, four, including Graves, are reporting that their seizures have decreased by 80% and more. There are also improvements in cognitive tests. People with epilepsy have a hard time remembering things, but some of the volunteers can now recall an entire series of pictures.

“It’s early, but it could be restorative,” says Cory Nicholas, a former laboratory scientist who is the CEO of Neurona. “I call it activity balancing and repair.”

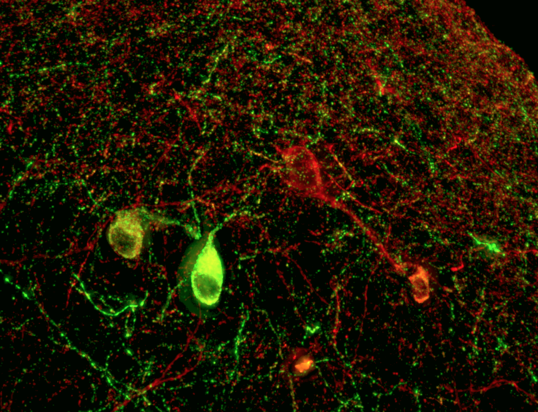

Starting with a supply of stem cells originally taken from a human embryo created via IVF, Neurona grows “inhibitory interneurons.” The job of these neurons is to quell brain activity—they tell other cells to reduce their electrical activity by secreting a chemical called GABA.

Graves got his transplant in July. He was wheeled into an MRI machine at the University of California, San Diego. There, surgeon Sharona Ben-Haim watched on a screen as she guided a ceramic needle into his hippocampus, dropping off the thousands of the inhibitory cells. The bet was that these would start forming connections and dampen the tsunami of misfires that cause epileptic seizures.

Ben-Haim says it’s a big change from the surgeries she performs most often. Usually, for bad cases of epilepsy, she is trying to find and destroy the “focus” of misbehaving cells causing seizures. She will cut out part of the temporal lobe or use a laser to destroy smaller spots. While this kind of surgery can stop seizures permanently, it comes with the risk of “major cognitive consequences.” People can lose memories, or even their vision.

That’s why Ben-Haim thinks cell therapy could be a fundamental advance. “The concept that we can offer a definitive treatment for a patient without destroying underlying tissue would be potentially a huge paradigm shift in how we treat epilepsy,” she says.

Nicholas, Neurona’s CEO, is blunter. “The current standard of care is medieval,” he says. “You are chopping out part of the brain.”

For Graves, the cell transplant seems to be working. He hasn’t had any of the scary “grand mal” attacks, that kind can knock you out, since he stopped drinking. But before the procedure in San Diego, he was still having one or two smaller seizures a day. These episodes, which feel like euphoria or déjà vu, or an absent blank stare, would last as long as half a minute.

Now, in a diary he keeps as part of the study to count his seizures, most days Graves circles “none.”

Other patients in the study are also telling stories of dramatic changes. A woman in Oregon, Annette Adkins, was having seizures every week; but after a transplant she’s nearly seizure free according to a report last year. Heather Longo, the mother of another subject, has also said her son had gone for periods without any seizures. She’s hopeful his spirits are picking up and said that his memory, balance, and cognition, had improved.

Getting consistent results from a treatment made of living cells is not going to be easy, however. One volunteer in the study saw no benefit, at least initially, while Graves’s seizures tapered away so soon after the procedure that it’s unclear whether the new cells could have caused the change, since it can takes weeks for them to grow out synapses and connect to other cells.

“I don’t think we really understand all the biology,” says Ben-Haim.

Neurona plans a larger study to help sift through cause and effect. Nicholas says the next stage of the trial will enroll 30 volunteers, half of whom will undergo “sham” surgeries. That is, they’ll all don surgical gowns, and doctors will drill holes into their skulls. But only some will get the cells; for the rest it will be play-acting. That is to rule out a placebo effect or the possibility that, somehow, simply passing a needle into the brain has some benefit.

Graves tells MIT Technology Review he is sure the cells helped him. “What else could it be? I haven’t changed anything else,” he says.

Now he is ready to believe he can get parts of his life back. He hopes to swim again. And if he can drive, he plans to move home to Louisville to be near his parents. “Road trips were always something I liked,” he says. “One of the plans I had was to go across the country. To not have any rush to it and see what I want.”

Now read the rest of The Checkup

Read more from MIT Technology Review’s archive

This summer, I checked into what 25 years of research using embryonic stem cells had delivered. The answer: lots of hype and no cures…yet.

Earlier this month, Cassandra Willyard wrote about the many scientific uses of “organoids.” These blobs of tissue (often grown from stem cells) mimic human organs in miniature and are proving useful for testing drugs and studying viral infections.

Our 2023 list of young innovators to watch included Julia Joung, who is discovering the protein factors that tell stem cells what to develop into.

There’s a different kind of stem cell in your bone marrow—the kind that makes blood. Gene-editing these cells can cure sickle-cell disease. The process is grueling, though. In December, one patient, Jimi Olaghere, told us his story.

From around the web

The share of abortions that are being carried out with pills in the US continues to rise, reaching 63%. The trend predates the 2022 Supreme Court decision allowing states to bar doctors from providing abortions. Since then, more women may have started getting the pills outside the formal health-care system. (New York Times)

Excitement over pricey new weight-loss drugs is causing “pharmaco-amnesia,” Daniel Engber says. People are forgetting there were already some decent weight-loss pills that he says were “half as good … for one-30th the price.” (The Atlantic)

There’s a bird flu outbreak among US dairy cattle. It’s troubling to see a virus jump species, but so far, it’s not that bad for cows. “It was kind of like they had a cold,” one source told the AP. (Associated Press)