“I felt too fat to be a feminist in public.”

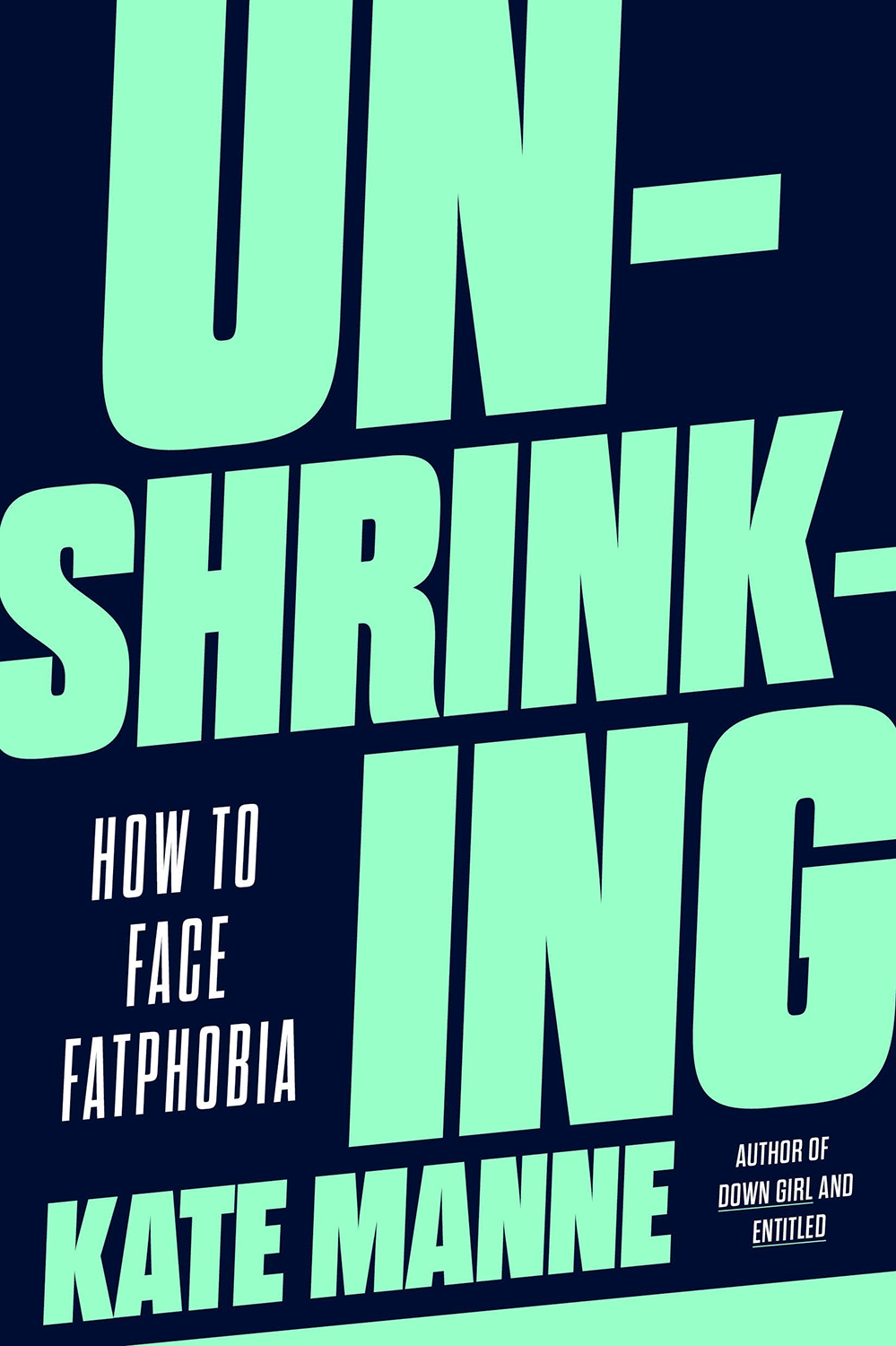

The startling admission appears in the opening paragraph of Kate Manne’s new book, Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia. With that single frank and sobering sentence, Manne, an associate professor of philosophy at Cornell, captures the pervasiveness of anti-fat bias—and its stifling impact.

Manne had tapped into the zeitgeist of #MeToo with her 2017 book, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, and was frequently called upon by the press to comment on current events like Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings. But in early 2019 she turned down the opportunity to go on an all-

expenses-paid publicity tour of London to promote the paperback release because she felt too self-conscious about her weight. The experience made her uncomfortably aware that even she, an Ivy League academic with a PhD from MIT, had internalized our society’s anti-fat bias.

“The combination of being publicly feminist and fat is a way of violating patriarchal norms and expectations in this very fundamental way,” she says, making it difficult to speak out “in a body that is ripe to be belittled and mocked.”

Manne grew up in Melbourne, Australia, where she recalls being called fat for the first time by a classmate in fifth grade PE class. She’d been fascinated by philosophy, which she describes as “thinking about thinking,” since the age of five, when a family friend who was a philosopher asked her why she was catching butterflies in a net and taking away their freedom. So she studied the subject in college and then wound up at MIT for grad school because she wanted to study with Sally Haslanger, a professor of philosophy and women’s and gender studies. “Sally proved to me, and continues to do so today, that philosophy can be rigorous, nuanced, socially aware, and politically savvy,” Manne says. After earning her PhD in 2011 and spending two years as a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows, she joined the faculty at Cornell, where her research focuses on moral, feminist, and social philosophy.

In Down Girl, Manne outlined the distinction between sexism (a patriarchal belief system) and misogyny (the enforcement of patriarchal norms by punishing women who violate them). The book was widely hailed: Rebecca Traister, author of Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, said Manne did “a jaw-droppingly brilliant job of explaining gender and power dynamics,” and in 2019 Manne was voted one of the world’s top 10 thinkers by the UK magazine Prospect. Her second book, Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women, made it onto the Atlantic’s list of the best 15 books of 2020 and Esquire’s list of 15 exceptional feminist books.

Haslanger isn’t at all surprised by her former graduate student’s success: “It was clear to those who knew her well that with her philosophical training, her beautiful writing, and her keen insight into the social domain, she would become a major public intellectual. And she has surpassed even our expectations.”

Nonetheless, says Manne, “it took 25 years for the personal piece of [feminism] to fall into place along with the political piece.” That personal aspect is chronicled in painful detail in Unshrinking, as Manne connects the dots between misogyny and the fatphobic bullying she suffered as a teen. “The form misogyny took was weaponized fatphobia against me as a slightly larger-than-average teen girl,” she explains.

“Since my early 20s, I have been on every fad diet. I have tried every weight-loss pill. And I have, to be candid, starved myself, even not so long ago,” Manne writes in the introduction to Unshrinking. “I can tell you precisely what I weighed on my wedding day, the day I defended my PhD dissertation, the day I became a professor, and the day I gave birth to my daughter. (Too much, too much, too much, and much too much, to my own mind then.) I even know what I weighed on the day I arrived in Boston—fresh off the plane from my hometown of Melbourne, Australia—to begin graduate school in philosophy, nearly twenty years ago.”

Although she had been aware of the work of fat activists, it was motherhood that finally pushed Manne to stop engaging in disordered eating and extreme dieting, and ultimately to write Unshrinking. She didn’t want her daughter “to bear witness to a mother trying to shrink herself in a futile and pointless and frankly sad way,” she says. In conducting research for the book, she came across some alarming statistics: by age six, more than half the girls in one study had worried about being fat, and another study found that by age 10, an astounding 80% of girls had been on a diet. Even many feminists “still want to shrink our bodies in ways that conform to patriarchal norms and expectations that are extremely hard to resist,” Manne says.

Unshrinking joins the growing literature on anti-fat bias, including the work of sociologist Sabrina Strings, whose book Fearing the Black Body details its racist origins, tracing the shift from the admiration of plumpness as a sign of wealth to the vilification of fat that she argues developed alongside the transatlantic slave trade. Like recent books by Aubrey Gordon and journalist Virginia Sole-Smith, Manne’s uses scientific research to debunk pervasive misconceptions—for example, about the extent to which people can control the size of their bodies—and even to counter the idea that obesity is a disease that requires a cure or large-scale policy response.

Research from as early as 1959 has shown that most people cannot sustain long-term weight loss. A recent piece in the journal Obesity finds that weight regain “occurs in the face of the most rigorous weight-loss interventions” and that “approximately half of the lost weight is gained back within 2 years and up to 70% by 5 years.” Not even those who undergo bariatric surgery, the researchers add, are immune to weight regain. Two physician researchers from Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania recently reported in Nature Metabolism, “Overall, only about 15% of individuals can sustain a 10% or greater non-surgical, non-pharmacological weight loss.”

Likewise, while exercise is beneficial for our bodies, a research review published in Diabetes Spectrum concludes it’s not firmly established that it plays a big role in helping people lose weight.

“I can tell you precisely what I weighed on my wedding day, the day I defended my PhD dissertation, the day I became a professor, and the day I gave birth to my daughter.”

And although the medical establishment has been saying for decades that obesity leads to diseases like diabetes and hypertension, Manne points out that the dynamics are complex and there is much that is still unknown. While being very heavy is correlated with increased mortality, she maintains that we cannot assume it is a direct cause. For example, researchers have found that diabetes is associated not only with obesity but with poverty, food insecurity, and even past trauma as well.

Manne’s argument is not that being fat is unassociated with health risks, but rather that the connection is oversimplified. Given that there’s no proven route to long-term weight loss for most people, she says, we should focus on treating people’s diagnosable problems (such as diabetes and heart disease) rather than stigmatizing them because of their size. But anti-fat bias is all too common among medical professionals, who often misdiagnose fat people’s actual health problems because they ignore their reported symptoms. The prospect of dealing with this prejudice can also discourage fat people from going to the doctor at all. In 2020, a review of scientific publications led an international multidisciplinary expert panel to conclude that weight bias can lead to discrimination, undermining people’s human and social rights as well as their health. The 36 experts pledged in Nature Medicine to work to end the stigma attached to obesity in their fields.

What is needed, Manne argues, is to dismantle diet culture, which not only does not make people thinner in the long term but appears to make them fatter: “The studies that I draw on in the book make a very clear empirical case that a really excellent way to gain weight is to diet.” For example, a 2020 review in the International Journal of Obesity suggests that dieting can lead to eventually regaining more weight than was lost, given how one’s metabolism reacts to food restriction. A better way to improve public health, Manne argues, is to reduce the bias against larger bodies and make public spaces more accessible for people of all sizes. While data on the potential effects is limited, one 2018 study suggests that a weight-neutral approach known as Health at Every Size (HAES) is beneficial for body image and quality of life.

As a philosopher, Manne offers novel insights by looking at the way fatness is framed as a moral issue. Western societies see fat people as moral failures because, it is assumed, they lack the willpower to eat healthy foods and exercise. Manne argues that we have been conditioned to feel disgust toward fat people, and that this disgust is both “socially contagious” and deeply ingrained. Furthermore, we don’t trust feelings of pleasure derived by eating, or we don’t believe we inherently deserve food that tastes good; instead, we think we have to “earn” it, usually by depriving ourselves. Indeed, most of us are subject to frequent moralizing about “good” and “bad” food—whether from friends, family members, or our own internal voices.

All of this is part of what Manne calls the “fallacy of the moral obligation to be thin.” Secular moral philosophy is “clear that happiness and pleasure are good things, which we should be increasing in the world and promoting,” she says. “There’s nothing shameful about something that feels good, that some people want intensely, as long as it doesn’t hurt others or deprive others.”

So if diet culture causes pain, deprivation, and eating disorders, Manne maintains, we have a moral obligation to avoid it and instead to derive pleasure from eating. She reasons, “If you do think of there being a kind of moral value in self-care, then we really ought to be satisfying our appetites by eating satisfying food, as well as nourishing our bodies for instrumental reasons.” In her book, she calls diet culture a “morally bankrupt practice.”

But Manne’s experience as a fat academic has shown that most highly educated people still cling tightly to the “pseudo-obligation to try to shrink ourselves,” she says. Stereotypes of fat people as lazy and dumb are particularly harmful in spaces where intellect is highly prized. Anti-fat bias is pronounced in her field, Manne believes, “because as much as we pretend in philosophy not to all be dualists, we value the mind much more than the body, and we’re deeply suspicious of the body.” Tracing this “philosophical disapproval of indulgence” back to Plato and Aristotle, she says: “We think of the body as something feminine, wild, out of control, irrational—not a source of wisdom, but a source of really antiphilosophical distraction that will prevent us from … using our minds to think deep thoughts.”

The default image of an academic is thin, white, male, and able-bodied, which “distorts both our sense of who can think important thoughts and … what intellectual authority really is,” Manne says. This makes being a fat woman in academia particularly fraught. Favorable student evaluations are critical for gaining tenure, and numerous studies have shown that students already tend to judge female professors more harshly.

UCLA sociology professor Abigail Saguy finds Manne’s work compelling because she writes in an accessible way, “really reaching beyond the ivory tower and communicating important and complex topics.” A decade ago, Saguy wrote What’s Wrong with Fat, and she has seen a rise in awareness about anti-fat discrimination. However, she also notes the co-optation of “body positivity” rhetoric by weight-loss companies and influencers in order to sell their products.

Of course, the biggest news in the weight-loss industry has been the explosion in popularity of injectable drugs like Ozempic, which was originally developed to treat type 2 diabetes. Although Ozempic can be life-changing for diabetics, as well as potentially for those with cardiovascular risks, Manne says, “the majority of people who are pursuing intentional weight loss via these drugs are not even in higher risk categories” based on their body mass index, or BMI. A measure of body fat based on height and weight, BMI classifies people as underweight, normal, overweight, or obese and has been deemed deeply flawed by the American Medical Association (AMA) since it relies on data collected from non-Hispanic white people and has been used in racist ways. Even so, Manne notes that an analysis of data from the US National Health Interview Survey showed that people in the “overweight” category actually have the lowest all-cause mortality (lower than those in the “normal” category) even after controlling for smoking and preexisting diseases. So there’s often no medical need for people in this group—about a third of the US population—to use weight-loss drugs, she says.

With enormous profits at stake—the valuation of Novo Nordisk, which makes Ozempic, exceeds Denmark’s annual GDP—companies are eager to promote the idea of an obesity “epidemic” that got a boost in 2013, when the AMA declared obesity a disease even though a council it had convened on the matter advised against doing so. “Obviously these companies have a massive incentive to overinflate the extent and the seriousness of the problem,” she says, adding that if people discontinue these drugs because their side effects are intolerable or they’re too expensive, “the weight is gonna come roaring back.”

Manne believes that while people are entitled to pursue intentional weight loss, no one should feel obligated to do so. And when fat influencers or activists lose weight in a very public way, she says, they further stigmatize fat people who choose the path of fat acceptance. A recent New York Times article buttresses her argument. Manne is worried about “a real reversal of the progress we’ve made in fat-activist communities,” fearing that it may be easier for doctors to prescribe drugs to fat patients than to reexamine their own long-held negative beliefs about them.

However, the positive feedback for Manne’s work suggests that it can make an impact. Roxane Gay, author of Hunger, proclaimed Unshrinking “an elegant, fierce, and profound argument for fighting fat oppression in ourselves, our communities, and our culture.” Booklist called it “a brilliant takedown of fatphobia” in its starred review. Manne is particularly heartened by readers who have told her that the book convinced them to stop dieting or helped them advocate for themselves—for example, by asking for an airplane seatbelt extender without shame. Progress may be slow, but it’s progress.